Blood Feathers in Birds

Blood feathers are a completely normal part of your bird's physiological process. Whether your bird is young or old or somewhere in between, they are present throughout its life. As a loving bird owner, however, it is important for you to understand what blood feathers are, how to identify them and what to do if one breaks.

A blood feather is, quite simply, an actively growing feather that contains a blood supply. When a new feather forms in the follicle, the live tissue has a central artery and a vein in order to supply nutrients to the growing feather. Once the feather has grown in completely, the blood vessels shrink and dry up as they are no longer needed by the fully formed feather.

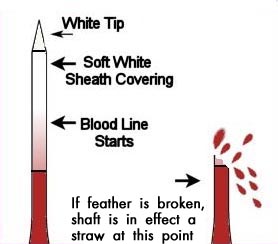

Fairly easy to identify, a blood feather has three main characteristics. One is that the quill or calamus is thicker and softer than a mature feather. The second characteristic is the length of the feather. Blood feathers are shorter than mature feathers since they have not yet grown to their full lengths. Third, and most easily identifiable, is the color of the shaft of the quill. Because there is an active blood supply to the feather, the quill shaft looks dark - maroon, bluish-purple, or black in color - instead of the usual white or clear look of a fully emerged feather.

Blood feathers are normally found on the wings and tail or on the crest of birds like cockatoos. Depending on what molting stage your bird is in dictates where the blood feather is located. Birds usually molt in a particular pattern so that they are always able to fly (whether in the wild or not). Baby birds, for instance, since growing their first set of feathers, have all of their blood feathers at one time all over their bodies. Adult birds may molt up to three times per year depending on the species. The pattern of molting follows an orderly progression. In a complete molt, the sequence usually starts with the inner primaries, continues with the secondaries and tail feathers and then finishes with the body feathers. Not to jeopardize their ability to fly, matched pairs of feathers are usually shed at the same time.

Problems arise with blood feathers when they are cut, broken, or bent. Because the feather has an artery and a vein, a damaged blood feather will bleed, often profusely. Some birds are prone to breaking blood feathers, particularly cockatiels and ring necks. Birds that are nervous, overcrowded in their cage or thrashing around are also apt to break blood feathers. Knowing your bird's habits and peculiarities, if any, can help prevent problems.

If your bird has a bleeding feather, the best way to handle the situation is to pull the feather. Pulling a blood feather is very painful, so it is not something you want to do unless absolutely necessary. With that in mind, you need to approach the situation with confidence. If you are uncertain, it is best to contact your veterinarian. If a bleeding feather is not cared for, your bird may bleed to death. A pair of needle-nosed pliers or a pair of hemostats are needed to remove a blood feather. Locate the break, gently grasp the feather near the base of the calamus (close to the body) and pull the feather straight out in the direction in which it is growing. This procedure usually requires two people, one to restrain the bird, preferably with a towel, and one to pull out the broken feather. Broken blood feathers may stop bleeding if left untouched, but as soon as they are bumped, bleeding usually commences. The only permanent solution is to gently, but firmly, pull the feather from its follicle and apply pressure to the follicle area with tissue, gauze, corn starch or Quick-Stop until the bleeding stops. If the bleeding does not stop, or the break is below the follicle, bring your bird to your veterinarian.

When you clip your bird's wings, make sure you examine each quill and identify that each shaft is not a blood feather before you cut. While cutting, leave the feather on each side of the blood feather long to help support it. Never clip up into the wing coverts, which leaves blood feathers unprotected, making them much more apt to break. If you do this each time, you minimize your chances of having a broken blood feather.

Ultimately, your bird will inevitably experience a broken blood feather at some point. It helps to watch your bird carefully when new feathers are coming in and visually inspect your bird daily. Even a quick once over in the morning and at night can help you catch a problem early. Keeping a pair of hemostats, cornstarch and gauze in a first-aid kit especially for your bird also makes handling the situation much easier.

[ Search Articles ] [ Article Index ]